This is Part 12 of “The Secret History of Silicon Valley,” the second of three posts about the rise of “risk capital” and how it came to be associated with what became Silicon Valley. Read Part I here, Part II here, Part III here, Part IVa here, Part IVb here, Part V here, Part VIa here, Part VIb here, Part VII here, Part VIII here, Part IX here, Part X here, and Part 11 here. See the Secret History bibliography for sources and supplemental reading.

———————–

The First Valley IPO’s

Silicon Valley first caught the eyes of east coast investors in the late 1950’s when the valley’s first three IPO’s happened: Varian in 1956, Hewlett Packard in 1957, and Ampex in 1958. These IPOs meant that technology companies didn’t have to get acquired to raise money or get their founders and investors liquid. Interestingly enough, Fred Terman, Dean of Stanford Engineering was tied to all three companies.

Varian made a high power microwave tube called the Klystron, invented by Terman’s students Russell and Sigurd Varian and William Hansen. In 1948 the Varian brothers along with Stanford professors Edward Ginzton and Marvin Chodorow founded Varian Corporation in Palo Alto to produce klystrons for military applications. Fred Terman and David Packard of HP joined Varian’s board.

Terman was also on the board of HP. Terman arranged for a research assistantship to bring his former student, David Packard, back from a job at General Electric in New York to collaborate with William Hewlett, another of Terman’s graduate students. Terman sat on the HP board from 1957-1973.

Ampex made the first tape recorders in the U.S (copied from captured German models,) and Terman was on its board as well. Ampex’s first customer was Bing Crosby who wanted to record his radio programs for rebroadcast (and had exclusive distribution rights.) Ampex business took off when Terman introduced Ampex founder Alex Poniatoff to Joseph and Henry McMicking. The McMicking’s bought 50% of Ampex for $365,000 (some liken this to the first VC investment in the valley.) McMicking and Terman introduced Ampex to the National Security Agency, and Ampex sales boomed when their audio and video recorders became the standard for Electronic Intelligence and telemetry signal collection recorders.

Meanwhile on the West Coast – “The Group” 1950’s

When Ampex was raising its money, in 1952, an employee of Fireman’s Fund in San Francisco, Reid Dennis, managed to put $15,000 in the deal. (Three-and-a-half years later it was worth $800,000.) Five years later Dennis and a small group of angel investors who called themselves “The Group” started investing in new electronics companies being formed in the valley south of San Francisco. These angels who were all working in their day jobs at various financial institutions, would invite startup electronics companies up to San Francisco to pitch their deals and they would invest an average of $100K per deal and help startups raise the rest – typically $250,000 in total.

The Group is worth noting for:

Investing their own private money,

Reid Dennis would found Institutional Venture Partners in 1974

First group specifically investing in the valley’s electronics industry

From the mid 1950s to mid 1960’s they invested in twenty-five companies. Eighteen of them were wildly successful

SBIC Act of 1958

During the cold war the launch of Sputnik-1 by the Soviet Union in 1957 both traumatized and galvanized the United States. Having the first earth satellite launched by a country that been portrayed as a third-world backwater with a bellicose foreign policy shocked the U.S. into believing it was behind the Soviet Union in innovation. In response, one of the many U.S. national initiatives (DARPA, NASA, Space Race, etc.) to spur innovation was a new government agency to fund new companies. The Small Business Investment Company (SBIC) Act in 1958 guaranteed that for every dollar a bank or financial institution invested in a new company, the U.S. government would invest three (up to $300,000.) So for every dollar that a fund invested, it would have four dollars to invest.

While SBIC’s were set up around the country, companies in Northern California including Bank of America, and American Express, began to set up SBIC funds to tap the emerging microwave and new semiconductor startups setting up shop south of San Francisco. And for the first time, private companies like Continental Capital, Pitch Johnson & Bill Draper and Sutter Hill were formed to take advantage of the government largesse from the SBA. Like all government programs, the SBIC was fond of paperwork, but it began to formalize, professionalize and standardize the way investors evaluated risk.

SBIC’s were worth noting for:

The good news – government money for startups encouraged a “risk capital” culture at large financial institutions.

The better news – government money encouraged private companies to form to invest in new startups

The bad news – the government was more interested in rules, regulations and accounting then startups (because some SBIC’s saw the government funds as a license to steal)

By 1968 over 600 SBIC funds provided 75% of all venture funding in the U.S.

In 1988 after the rise of the limited partnership that number would be 7%.

Limited Partnerships

By the end of the 1950’s there was still no clear consensus about how to best organize an investment company for risky ventures. Was it like George Doriot’s ARD venture fund – a publicly traded closed end mutual fund? Was it using government money as a private SBIC firm? Or was it some other form of organization? Many investors weren’t interested in working for a large company for a salary and bonus, and most hated the paperwork and salary limitations that the SBIC imposed. Was there some other structure?

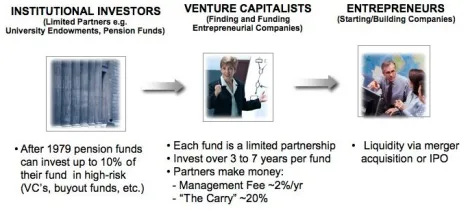

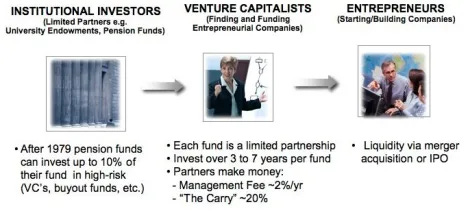

The limited partnership offered one way to structure an investment company. The fund would have limited life. It would charge its investors annual “management fees” to pay for the firm’s salaries, building, etc. In a typical venture fund, the partners receive a 2% management fee.

But the biggest innovation was the “carried interest” (called the “carry”.) This is where the partners would make their money. They would get a share of the profits of the fund (typically 20%.) For the first time venture investors would have a very strong performance incentive.

In 1958 General William Draper, Rowan Gaither (founder of the RAND corporation) and Fred Anderson (a retired Air Force general) founded Draper, Gaither and Anderson, Silicon Valley’s (and possible the worlds) first limited partnership. The venture firm was funded by Laurance Rockefeller and Lazard Freres, but after some dispute lost to the sands of time, Rockefeller pulled his financing, and the firm was dissolved after the first fund.

The first limited partnership that lasted for a while was formed by Davis and Rock in 1961. Arthur Rock, an investment banker at Hayden Stone in New York (who helped broker the financing of Fairchild) moved out to San Francisco in 1961 and partnered with Tommy Davis. Davis (an ex-WWII OSS agent) then a VP at the Kern Land Company got involved with investing in technology companies through Fred Terman. Davis’s first investment in 1957 was Watkins-Johnson (the maker of microwave Traveling Wave Tubes for electronic intelligence systems) where he sat on its board with Fred Terman. Rock and Davis would raise a $5M fund from east coast institutions and while they invested only $3.4 million of it by the time they dissolved their partnership in 1968 – they returned $90 million to their limited partners – a 54% compound growth rate.

Limited partnerships are worth noting for:

By the 1970’s the limited partnership would become the preferred organizational form for venture investors

The “carried interest” (the “carry”) assured that the venture partners would only make real money if their investments were successful. Aligning their interests with their limited investors and the entrepreneurs they were investing in.

The limited life of each fund; 7-10 years of which 3-5 years would be spent actively investing, focused the firms on investments that could reasonably expect to have “exits” during the life of the fund.

The limited life of each fund allowed venture firms to be flexible. They could change the split of the carry in follow on funds, add partners with carry in subsequent funds, change investing strategy and focus in follow-on funds, etc.

Silicon Innovation Collides with Risk Capital

Lacking a “risk capital” infrastructure in the 1950’s military contracts and traditional bank loans were the only options microwave startups had for capital. The first semiconductor companies couldn’t even get that – Shockley and Fairchild could only be funded through corporate partners. But by the 1960’s the tidal wave of semiconductor startups would find a valley with a growing number of SBIC backed venture firms and limited partnerships.

A wave of silicon innovation was about to meet a pile of risk capital.

More on this in Part XIII of the Secret History of Silicon Valley.

Steve - why not make this an ebook? Kindle or otherwise, would be great to read in one piece, I've read portions but only according to which email I've opened, and out of sequence too