This is Part IV of how I came to write “The Secret History of Silicon Valley.”

Read Part III, Part II here and Part I here.

All You Can Read Without a Library Card

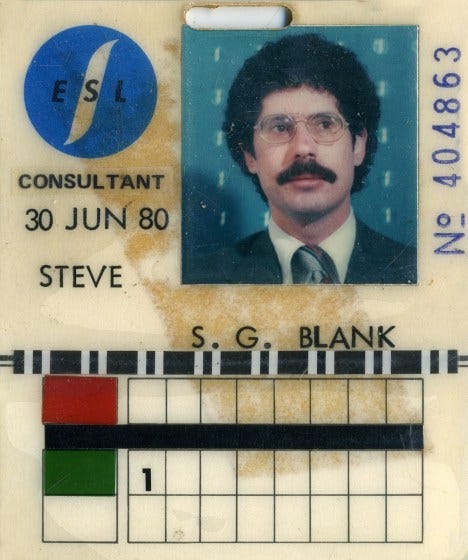

It was 1978. Here I was, a very junior employee of ESL, a company with its hands in the heart of our Cold War strategy. Clueless about the chess game being played in Washington, I was just a minion in a corporate halfway house in between my military career and entrepreneurship.

ESL sent me overseas to a secret site run by one of the company’s “customers.” It was so secret the entire site was could have qualified as one of Dick Cheney’s “undisclosed locations.” As a going away gift my roommates got me a joke disguise kit with a fake nose, glasses and mustache.

The ESL equipment were racks of the latest semiconductors designed into a system so complicated that the mean-time-between-failure was measured in days. Before leaving California, the engineers gave me a course in this specialized receiver design. Since I had spent the last four years working on advanced Air Force electronic intelligence receivers, I thought there wouldn’t be anything new. The reality was pretty humbling. Here was a real-world example of the Cold War “offset strategy.” Taking concepts that had been only abstract Ph.D theses, ESL had built receivers so sensitive they seemed like science fiction. For the first time we were able to process analog signals (think radio waves) and manipulate them in the digital domain. We were combining Stanford Engineering theory with ESL design engineers and implementing it with chips so new we were debugging the silicon as we were debugging the entire system. And we were using thousands of chips in a configuration no rational commercial customer could imagine or afford. The concepts were so radically different that I spent weeks dreaming about the system theory and waking up with headaches. Nothing I would work on in the next 30 years was as bleeding edge.

Now half a world away on the customer site, my very small role was to keep our equipment running and train the “customer.” As complex as it was, our subsystem was only maybe one-twentieth of what was contained in that entire site. Since this was a location that worked 24/7, I was on the night shift (my favorite time of the day.) Because I could get through what I needed to do quickly, there wasn’t much else to do except to read. As the sun came up, I’d step out of the chilled buildings and go for an early morning run outside the perimeter fence to beat the desert heat. As I ran, if I looked at the base behind the fence I was staring at the most advanced technology of the 20th century. Yet if turned my head the other way, I’d stare out at a landscape that was untouched by humans. I was in between the two thinking of this movie scene. (At the end of a run I used to lay out and relax on the rocks to rest – at least I did, until the guards asked if I knew that there were more poisonous things per square foot here than anywhere in the world.)

Before long I realized that down the hall sat all the manuals for all the equipment at the entire site. Twenty times more technical reading than just my equipment. Although all the manuals were in safes, the whole site was so secure that anybody who had access to that site had access to everything – including other compartmentalized systems that had nothing to do with me – and that I wasn’t cleared for. Back home at ESL control of compartmentalized documents were incredibly strict. As a contractor handling the “customer’s” information, ESL went by the book with librarians inside the vaults and had strict document access and control procedures. In contrast, this site belonged to the “customer.” They set their own rules about how documents were handled, and the safes were open to everyone.

I was now inside the firewall with access to everything. It never dawned on me that this might not be a good idea.

Starting on the safe on the left side, moving to the safe on the right side, I planned to read my way through every technical manual of every customer system. We’re talking about a row of 20 or so safes each with five drawers, and each drawer full of manuals. Because I kept finding interesting connections and new facts, I kept notes, and since the whole place was classified, I thought, “Oh, I’ll keep the notes in one of these safes.” So I started a notebook, dutifully putting the classification on the top and bottom of each page. As I ran into more systems I added the additional code words that on the classification headers. Soon each page of my notes had a header and footer that read something like this: Top Secret / codeword/ codeword / codeword / codeword / codeword / codeword / codeword.

I was in one of the most isolated places on earth yet here I was wired into everywhere on earth. Coming to work I would walk down the very long, silent, empty corridors, open a non-descript door and enter the operations floor (which looked like a miniature NASA Mission Control), plug a headset into the networked audio that connected all the console operators — and hear the Rolling Stones “Sympathy for the Devil.” (With no apparent irony.) But when the targets lit up, the music and chatter would stop, and the communications would get very professional.

Nine months into my year tour, and seven months into my reading program, I was learning something interesting every day. (We could do what!? From where??) Then one day I got a call from the head of security to say, “Hey, Steve can you stop into my office when you get a chance?”

Are These Yours?

Now this was a small site, about 100-200 people, and here was the head of security was asking me over for coffee. Why how nice, I thought, he just wants to get to know me better. (Duh.) When I got to his office, we made some small talk and then he opened up a small envelope, tapped it on a white sheet of paper, and low and behold, three or four long black curly hairs fall out. “Are these yours?” he asked me.

This the one of the very few times I’ve been, really, really impressed. I said, “Why yes they are, where did you get them?” He replied, ‘They were found in the ‘name of system I should have absolutely no knowledge or access to’ manuals. Were you reading those?” I said, “Absolutely.” When he asked me, “Were you reading anything else?” I explained, “Well I started on the safe on the left, and have been reading my way through and I’m about three quarters of the way done.”

Now it was his turn to be surprised. He just stared at me for awhile. “Why on earth are you doing that?” he said in a real quiet voice. I blurted out, “Oh, it’s really interesting, I never knew all this stuff and I’ve been making all these notes, and …” I never quite understood the word “startled” before this moment. He did a double-take out of the movies and interrupted me, “You’ve been making notes?” I said, “Yeah, it’s like a puzzle,” I explained. “I found out all this great stuff and kept notes and stored in the safe on the bottom right under all the…” And he literally ran out of the office to the safes and got my notebook and started reading it in front of me.

And the joke (now) was that even though this was the secret, secret, secret, secret site, the document I had created was more secret than the site.

While the manuals described technical equipment, I was reading about all the equipment and making connections and seeing patterns across 20 systems. And when I wasn’t reading, I was also teaching operations which gave me a pretty good understanding of what we were looking for on the other side. At times we got the end product reports from the “customer” back at the site, and these allowed me to understand how our system was cued by other sensors collecting other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, and to start looking for them, then figuring out what their capabilities were.

Pattern Recognition

As I acquired a new piece of data, it would light up a new set of my neurons, and I would correlate it, write it down and go back through reams of manuals remembering that there was a mention elsewhere of something connected. By the time the security chief and I were having our ‘curly hairs in the envelope’ conversation, not only did I know what every single part of our site did, but what scared the security guy is that I had also put together a pretty good guesstimate of what other systems we had in place worldwide.

For one small moment in time, I may have assembled a picture of the sum of the state of U.S. signals intelligence in 1978 − the breadth and depth of the integrated system of technical assets we had in space, air, land, and other places all focused on collection. (If you’re a techie, you’d be blown away even 40 years later.) And the document that the head of security had in his hand and was reading, as he told me later, he wasn’t cleared to read – and I wasn’t cleared to write or see. I’m sure I knew just a very small fraction of what was going on, but still it was much more than I was cleared for.

At the time this seemed quite funny to me probably because I was completely clueless about what I had done, and thought that no one could believe there was another intent. But in hindsight, rather than the career I did have, I could now just be getting out of federal prison. It still sends shivers up my back. After what I assume were a few phone calls back to Washington, the rules said they couldn’t destroy my notebook, but they couldn’t keep it at the site either. Instead my notebook was couriered to Washington – back to the “customer.” (I picture it still sitting in some secure warehouse.) The head of security and I agreed my library hours were over and I would take up another hobby until I went home.

Thank you to the security people who could tell the difference between an idiot and a spy.

When I got back to Sunnyvale, my biggest surprise was that I didn’t get into trouble. Instead someone realized that the knowledge I had accumulated could provide the big picture to brief new guys “read in” to this compartmentalized program. Of course I had to work with the customer to scrub the information to get its classification back down to our compartmental clearance. (My officemate who would replace me on the site, Richard Farley, would go on to a more tragic career.) I continued to give these briefings as a consultant to ESL even after I had joined my first chip startup; Zilog.

Two Roads Diverged in a Wood and I took the Road Less Traveled By, And That Has Made All the Difference

Extraordinary times bring extraordinary people to the front. Bill Perry the founder of ESL (and later Secretary of Defense) is now acknowledged as one of the founders of the entire field of National Reconnaissance, working with the NSA, CIA and the NRO to develop systems to intercept and evaluate Soviet missile telemetry and communications intelligence.

ESL had no marketing people. It had no PR agency. It shunned publicity. It was the model for almost every military startup that followed, and its alumni who lived through its engineering and customer-centric culture had a profound effect on the rest of the valley, the intelligence community and the country. And during the Cold War it sat side by side with commercial firms in Silicon Valley, with its nondescript sign on the front lawn. It had Hidden in Plain Sight.

As for me, after a few years I decided that into was time to turn swords into plowshares. I left ESL and the black world for a career in startups; semiconductors, supercomputers, consumer electronics, video games and enterprise software.

I never looked back.

It would be decades before I understood what an extraordinary company I had worked for.

Thank you Bill Perry for one heck of a start in Silicon Valley.

I was 24.

“The Secret History of Silicon Valley” continues with Part IVb here.

A very entertaining story Steve, and truly incredible opportunity to work at the leading edge.