This is Part II of “The Secret History of Silicon Valley.” Read Part I here, Part II here, Part III here, Part IVa here, Part IVb here, Part V here, Part VIa here, Part VIb here, Part VII here, Part VIII here, Part IX here and Part X here. See the Secret History bibliography for sources and supplemental reading.

This is the first of a few posts about the rise of “risk capital” and how it came to be associated with what became Silicon Valley.

———————–

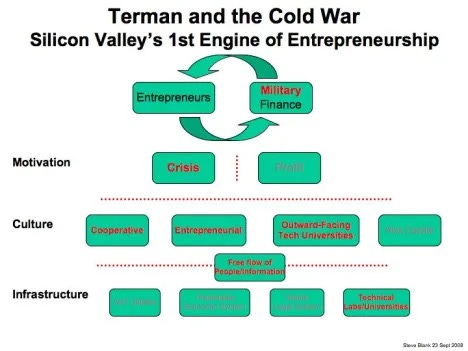

Building Blocks of Entrepreneurship

By the mid 1950’s the groundwork for a culture and environment of entrepreneurship in the United States was taking shape on the east and west coasts and of all places in and around Minneapolis. Stanford and MIT were building on the technology breakthroughs of World War II and graduating a generation of engineers into a consumer and cold war economy that seemed limitless. Meanwhile in Minneapolis one of the first computer companies was formed to help break codes for the National Security Agency. On the east and west coast communication between scientists, engineers and corporations was relatively open, and ideas flowed freely. There was an emerging culture of cooperation and entrepreneurial spirit.

Stanford Commercialization Strategy

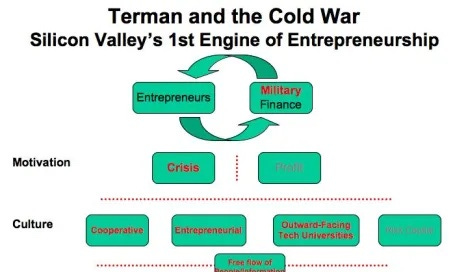

At Stanford, Dean of Engineering Fred Terman wanted companies outside of the university to take Stanford’s prototype microwave tubes and electronic intelligence systems and build production volumes for the military. While existing companies took some of the business, often it was a graduate student or professor who started a new company. The motivation in the mid 1950’s for these new microwave startups was a crisis – we were in the midst of the cold war and the United States military and intelligence agencies were rearming as fast as they could.

Yet one of the most remarkable things about the boom in microwave and first silicon startups occurring in the 1950’s and 60’s Silicon Valley was that it was done without venture capital or public offerings. There was none. Funding for the companies spinning out of Stanford’s engineering department in the 1950’s benefited from the tight integration and web of relationships between Fred Terman, Stanford, the U.S. military and intelligence agencies and defense contractors.

These technology startups had no risk capital – just customers/purchase orders from government contractors/ military services/ or our intelligence agencies.

This post is about the rise of “risk capital” and how it came to be associated with what became Silicon Valley. (It is interesting that during the 50’s and 60’s other innovation clusters were using different methods – the first Venture Capital firm was in Boston, and subordinated debt and public offerings were common in Minneapolis.)

Risk Capital via Family Money – 1940’s

During the 1930’s, the heirs to U.S. family fortunes made in the late 19th century – Rockefeller, Whitney, Bessemer – started to dabble in personal investments in new, risky ventures. Post World War II this generation recognized that:

Technology spin-offs coming out of WWII military research and development could lead to new, profitable companies

Entrepreneurs attempting to commercialize these new technologies could not get funding; (commercial and investment banks didn’t fund new companies, just the expansion of existing firms,) and existing companies would buy up entrepreneurs and their ideas, not fund them

There was no organized company to seek out and evaluate new venture ventures, manage investments in them and nurture their growth.

Several wealthy families in the U.S. set up companies to do just that – find and formalize investments in new and emerging industries.

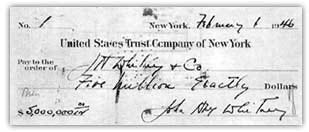

In 1946 Jock Whitney started J.H. Whitney Company by writing a personal check for $5M and hiring Benno Schmidt as the first partner (Schmidt turned Whitney’s description of “private adventure capital” into the term “venture capital”).

That same year Laurance Rockefeller founded Rockefeller Brothers, Inc., with a check for $1.5 million. (23 years later they would rename the firm Venrock.)

Bessemer Securities, set up to invest the Phipps family fortune (Phipps was Andrew Carnegie’s partner,)

These early family money efforts are worth noting for:

They were “risk capital,” investing where others feared

They invested in a wide variety of new industries – from orange juice to airplanes

They almost exclusively focused on the East Coast

They used family money as the source of their investment funds

East Coast Venture Capital Experiments

In 1946, George Doriot, founded what is considered the first “venture capital firm” – American Research & Development (ARD). A Harvard Business School professor and early evangelist for entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship, Doriot was the Fred Terman of the East Coast. Doroit had the right idea with ARD (funding startups out of MIT and Harvard and raising money from outsiders who weren’t part of a private family) but picked the wrong model for raising capital for his firm. ARD was a publicly traded venture capital firm (raising $3.5 Million in 1946 as a closed-end mutual fund) which meant ARD was regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC.) For reasons too numerous to mention here, this turned out to be a very bad idea. (It would be another three decades of experimentation before the majority of venture firms organized as limited partnerships.)

In 1958, in Minneapolis, Midwest Technical Development Corporation was founded to emulate Doriot’s ARD venture firm. And by 1961 they were one of the most successful venture firms in the country investing in National Semiconductor, one of Silicon Valley’s earliest chip companies. Like ARD, the firm ran afoul of the SEC and closed in 1963.

The region around Boston’s Route 128 would boom in the 1950’s-70’s with technology startups, many of them funded by ARD. ARD’s most famous investment was the $70,000 they put into Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) in 1957 for 77% of the company that was worth hundreds of millions by its 1968 IPO. It wasn’t until the rise of the semiconductor industry and a unique startup culture in Silicon Valley that entrepreneurship became associated with the West Coast.

Doriot and American Research and Development are worth noting for:

Some of the very early VC’s got their venture capital education at Harvard as Doriot’s students (Arthur Rock, Peter Crisp, Charles Waite.)

ARD was almost exclusively focused on the East Coast

ARD proved that institutional investors, not just family money had an appetite for investing into venture capital firms.

Corporate Finance

One of the ironies in Silicon Valley is that the two companies which gave birth to its entire semiconductor industry weren’t funded by venture capital. Since neither of these startups were yet doing any business with the military—and venture capital as we know it today did not exist, they had to look elsewhere for funding. Instead, in 1956/57, Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory and Fairchild Semiconductor were both funded by corporate partners — Shockley by Beckman Instruments, Fairchild by Fairchild Camera and Instrument.

More on the rise of SBIC’s, Limited Partnerships, the venture capital industry as we know it today, and its influence on the creation of the Department of Defense of Office of Strategic Capital in Part XII of the Secret History of Silicon Valley.

Steve, your history of Silicon Valley should be a book! Love your posts. It would be great to catch up together sometime. Happy Holidays, Norman