The Secret History of Silicon Valley Part 15: Agena -The Secret Space Truck, Ferret's and Stanford

This is Part 15 of “The Secret History of Silicon Valley,” Read Part I here, Part II here, Part III here, Part IVa here, Part IVb here, Part V here, Part VIa here, Part VIb here, Part VII here, Part VIII here, Part IX here, Part X here, Part XI here, Part XII here, Part XIII here and Part XIV here. See the Secret History bibliography for sources and supplemental reading.

By the early 1960’s Lockheed Missiles Division in Sunnyvale was quickly becoming the largest employer in what would be later called Silicon Valley. Along with its publically acknowledged contract to build the Polaris Submarine Launched Ballistic Missile (SLBM), Lockheed was also secretly building the first photo reconnaissance satellites (codenamed CORONA) for the CIA in a factory in East Palo Alto.

It was only a matter of time before Stanford’s Applied Electronics Lab research on Electronic and Signals Intelligence and Lockheed’s missiles and spy satellites intersected. Here’s how.

Lockheed Agena

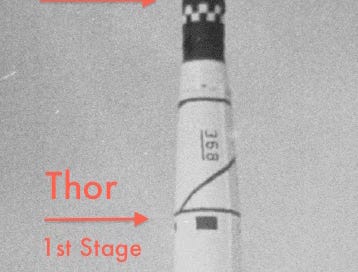

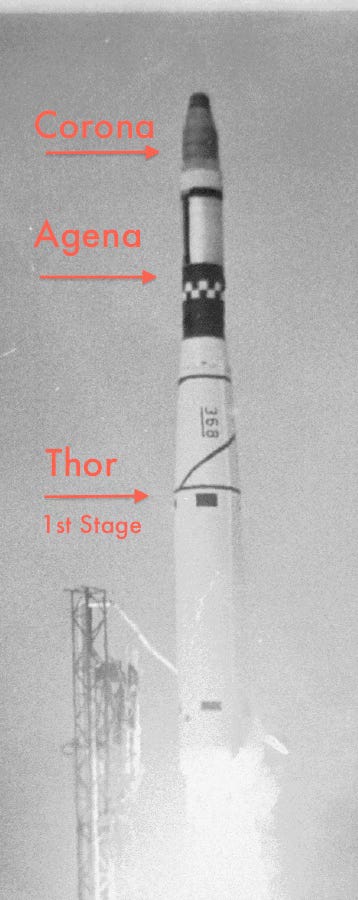

In addition to the CORONA CIA reconnaissance satellites, Lockheed was building another assembly line, this one for the Agena – a space truck. The Agena sat on top of a booster rocket (first the Thor, then the Altas and finally the Titan) and had its own rocket engine that would help haul the secret satellites into space. The engine (made by Bell Aerosystems) used storable hypergolic propellants so it could be restarted in space to change the satellite’s orbit. Unlike other second stage rockets, once in orbit, the CORONA reconnaissance satellite would stay attached to the Agena which stabilized the satellite, pointed it in the right location, and oriented it in the right direction to send its recovery capsule on its way back to earth.

The Agena would be the companion to almost all U.S. intelligence satellites for the next decade. Three different models were built and for over a decade nearly four hundred of them (at the rate of three a month) would be produced on an assembly line in Sunnyvale, and tested in Lockheed’s missile test base in the Santa Cruz mountains.

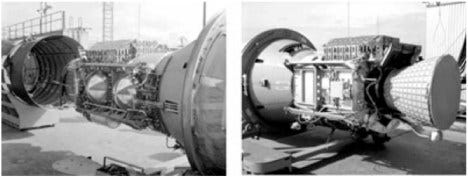

Agena Ferrets – Program 11/Project 989

As Lockheed engineers gained experience with the Agena and the CORONA photo reconnaissance satellite, they realized that they had room on a rack in the back of the Agena to carry another payload (as well as the extra thrust to lift it into space). By the summer of 1962, Lockheed proposed a smaller satellite that could be deployed from the rear of the Agena. This subsatellite was called Program 11, or P-11 for short (also called Project 989.) The P-11 subsatellite weighed up to 350lbs, had its own solid rockets to boost it into different orbits, solar arrays for power and was stabilized by either deploying long booms or by spinning 60-80 times a second.

And they had a customer who couldn’t wait to use the space. While the CORONA reconnaissance satellites were designed to take photographs from space, putting a radar receiver on a satellite would enable it to receive, record and locate Soviet radars deep inside the Soviet Union. For the first time, the National Security Agency (working through the National Reconnaissance Office) and the U.S. Air Force could locate radars which would threaten our manned bombers as well as those that might be part of an anti-ballistic missile system. Most people thought the idea was crazy. How could you pick up a signal so faint while the satellite was moving so rapidly? Could you sort out one radar signal from all the other noise? There was one way to find out. Build the instruments and have them piggyback on the Agena/CORONA photo reconnaissance satellites.

But who could quickly build these satellites to test this idea?

Stanford and Ferrets

Just across the freeway from Lockheed’s secret CORONA assembly plant in Palo Alto, James de Broekert was at Stanford Applied Electronics Laboratory. This was the Lab founded by Fred Terman from his WWII work in Electronic Warfare.

“This was an exciting opportunity for us,” de Broekert remembered. “Instead of flying at 10,000 or 30,000 feet, we could be up at 100 to 300 miles and have a larger field of view and cover much greater geographical area more rapidly. The challenges were establishing geolocation and intercepting the desired signals from such a great distance. Another challenge was ensuring that the design was adapted to handle the large number of signals that would be intercepted by the satellite. We created a model to determine the probability of intercept on the desired and the interference environment from the other radar signals that might be in the field of view, de Broekert explained.

“My function was to develop the system concept and to establish the system parameters. I was the team leader, but the payloads were usually built as a one-man project with one technician and perhaps a second support engineer. Everything we built at Stanford was essentially built with stockroom parts. We built the flight-ready items in the laboratory, and then put them through the shake and shock fall test and temperature cycling…”

Like the cover story for the CORONA (which called them Discoverer scientific research satellites), the first three P-11 satellites were described as “science” missions with results published in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

Just fifteen years after Fred Terman had built Electronic Intelligence and Electronic Warfare systems for bombers over Nazi Germany, Electronic Intelligence satellites were being launched in space to spy on the Soviet Union.

Close to 50 Ferret subsatellites were launched as secondary payloads aboard Agena photo reconnaissance satellites.

SAMOS/Project 102/698BK/Program 770 – Low Earth Orbit Agena “Heavy” Ferrets

Lockheeds Agena’s would play another role in overhead reconnaissance – they would carry Air Force heavy ferrets (Electronic Intelligence payloads) as part of the SAMOS program.

In the 1960’s the U.S. Air Force Strategic Air Command (SAC) needed to understand the electronic order of battle inside the Soviet Union so B-52 bombers could evade or jam those radars on the way to their targets. (Where were the Soviet early warning radars? The ground controlled intercept radars? What are their technical characteristics?) Other parts of the government wanted to know details about Soviet Anti Ballistic Missile (ABM) systems.

SAMOS originally was supposed to provide photo reconnaissance from space by developing film in orbit and electronically scanning it and beaming it to the ground. For the early 1960’s this approach turned out to be a technical bridge too far. (The U.S. wouldn’t beam down photo reconnaissance images until the KH-11 satellites in December 1976.) The CIA’s CORONA program, which dropped film canisters from space turned out to be a more efficient way to solve the problem. With CORONA successful, and results from the electronic intelligence sensors on P-11 program providing useful information, the Air Force pivoted from photo reconnaissance to electronic reconnaissance, which had already been a secondary SAMOS payload.

32 dedicated Agena heavy ferret missions were launched from the the early 1960’s to the end of the program in 1972.

Ferret Entrepreneur

After student riots in April 1969 at Stanford shut down the Applied Electronics Laboratory, James de Broekert left Stanford. He was a co-founder of three Silicon Valley military intelligence companies: Argo Systems, Signal Science, and Advent Systems.

In 2000 the National Reconnaissance Office recognized James de Broekert as a “pioneer” for his role in the “establishment of the discipline of national space reconnaissance.”

See part 16 “Balloon Wars” of the Secret History of Silicon Valley next.

Agena was also used as the target vehicle for the world's first docking of two vehicles in space. Several others followed during Project Gemini, which also used the Titan II booster. The first docking was performed on Gemini VIII, by a guy named Neil Armstrong. Gemini XI used the Agena "space truck" to break an altitude record with an apogee of 853 miles (1,373 km). At that altitude, the horizon would begin to converge, revealing the circle of the earth.

Steve, this series is incredible. Thank you for your efforts with this. My first memory of Silicon Valley was the AMPEX building off of 101 and this is revealing the hidden mystery long before then.